There is something really odd about a character that doesn’t talk.

Silence holds a unique tension. Stillness is the same. They create a wonderful expectancy.

Think of being in any situation with a group of people, one of whom never speaks. What would you think of that person?

I not against talking. I’m definitely not against sound. (In the double act that I work in, my partner talks for the entire show and we pay a huge amount of attention to creating rhythm from the natural sound of our movement, our props and our environment.)

I don’t want to make characters that are silent for the sake of being different. For me silence is not an “experimental” choice.

On the contrary, we spend most of our days in silence. Much of our interaction is non-verbal. A huge amount of our observation of other people is of their movement. We’ve all sat in a cafe window people watching!

So we don’t need to make fraudulent “mime” scenes. We can just make scenes where talking naturally is absent. Most obviously, when people are on their own and when people are watched from afar. Or you could set a scene on a deafening oil rig. Or even where two hostages have their mouths taped. (These last two are less interesting to me as they will inevitably involve attempts at talking through mime.)

I enjoy the fun of interpretating or “working out the puzzle” of non-verbal scenes. And equally I love the creative puzzle of making clear inferences without resorting to pointing or unrealistic mime!

As noted in a previous blog, I love the freedom given to the audience to be vocal – not worrying about interrupting the performer or other audience members.

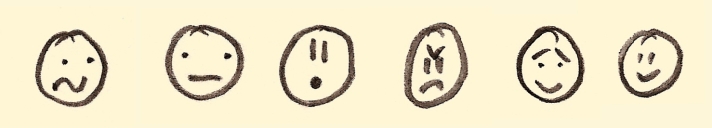

And, finally, but most importantly for me, there is the mysterious anonymity given to a character who we cannot hear. In watching something without the extra information given by the voice, we infer our own ideas about their personality and psychology. Once a character speaks, it is as though the mask slips, and we are presented with something different – something more obvious and less animalistic. Maybe less unpredictable. (I always feel like Chaplin has a great wild animal quality.)

Is there perhaps something more universal about the non-verbal? Do we avoid projecting our preconceptions about people with certain accents and vocal qualities? Does it allow us to relate more deeply to the character as a result?

To conjure a simple example, imagine watching people on the road from up on a bridge. You see someone waiting, then someone arrives to stand next to him. Another person stands on the other side of the first. The last two exchange glances.

If I was watching that from afar I would be captivated, and a little anxious. And it is that feeling of interpreting what you are watching and not hearing that I find so thrilling.

But this doesn’t mean that everything is about a mysterious narrative. So long as the viewer believes that what they are watching is realistic – or at least consistent – you can explore an extraordinary world of subtle and outlandish behaviour.

Jacques Tati is probably the greatest exponent of this style of film-making. His use of “anonymous” behaviour is fascinating. He often uses a character that is a “watcher of the action”. In Jour de Fete there is an artist and an old lady. In Les Vacances de M. Hulot many of the characters watch each other. And it interesting to read that in French art, there is a well known character called “le flâneur” – someone who spends his time drifting around people watching.

There is a great example of Tati’s vision from 30 seconds:

The exclusion of words has a long tradition, particularly in France where the use of words was banned in theatre unless specifically licenced. This resulted in the French traditions of mime and pantomime. such as the manifesto of French physical performer Étienne Decroux in which he suggested that words be banned from theatre completely for a few years so that actors could learn to use their bodies effectively.

My exclusion of words is not about artistic resistance training! It is about accessing an unusual experience of interpreting what you are watching and a freedom to vocalise as an audience.

Am I being too fussy?! Or do you get a unique experience from watching non-verbal comedy?

Please let me know what you think!